The purpose of this feature is to give scout leaders, educators and naturalists an idea of some of the natural events coming up each month. We will try to cover a variety of natural events ranging from sky events to calling periods of amphibians, bird and mammal watching tips, prominent wildflowers and anything else that comes to mind. We will also note prominent constellations appearing over the eastern horizon at mid-evening each month for our area for those who would like to learn the constellations. If you have suggestions for other types of natural information you would like to see added to this calendar, let us know! Note: You can click on the hyperlinks to learn more about some of the featured items. To return to the Calendar, hit the "back" button on your browser, NOT the "back" button on the web page. All charts are available in a "printer friendly" mode, with black stars on a white background. Left clicking on each chart will take you to a printable black and white image. Please note that images on these pages are meant to be displayed at 100%. If your browser zooms into a higher magnification than that, the images may lose quality. Though we link book references to nationwide sources, we encourage you to support your local book store whenever possible.

Notes and Images From June 2015 This spring and summer we've been reacquainting ourselves with the planets. We imaged Jupiter and Saturn in May, and with the New Horizons spacecraft rapidly closing on Pluto, we thought it would be nice to image it as well. Pluto is in Sagittarius, in a little asterism known to amateur astronomers as "the teaspoon." The teaspoon is just above a larger asterism called "the teapot." Both are shown in the star chart below titled "Summer Messier Objects." The position of Pluto is marked with a red dot, but remember it is much too faint to be seen with the naked eye or a small telescope. Pluto is so tiny and far away that it is essentially just a point of light in an Earth-based telescope. At a distance of almost three billion miles, its globe is only about 0.1 arc-seconds across. It's also quite faint, between 14th and 15th magnitude. It looks like a very faint star, and to see it visually will probably require a 12 inch telescope. The long exposure times necessary for Pluto make it easier to image with our deep sky telescope, the 12.5 inch Newtonian. The first couple of weeks in June seemed like one long series of thunderstorms. But on June 14th we had a clear, pretty night when we ran our Tennessee Amphibian Monitoring Program route. The next night was almost as good, so I rolled the roof off of the observatory and prepared the scope. Since I had not used this telescope for a while I decided to take an image of the globular cluster Messier 10 in Ophiuchus as a tune-up before attempting Pluto. The scope did well, going through all of its automated sub-routines without a hitch. It acquired 60 minutes of data on M10, periodically pausing to refocus itself and then returning to the cluster.

Messier 10 is not the brightest globular cluster in the summer sky, but I think it's a pretty cluster. This cluster and nearby Messier 12 fit into the same binocular field of view and can be seen as faint misty spots on clear summer nights. Here at our farm, they are not hard to find in our 10x50 binoculars. The telescope finished up on Messier 10 around midnight. By this time I was getting a little tired. I started the scope on the Pluto run and then went to bed. Again, the scope imaged faithfully all through the morning hours, also taking some calibration frames before parking itself as the Sun came up. It wound up with 160 minutes of data in 10-minute sub-exposures. The image is shown at right. The field of view is about 16 arc-minutes wide, or about one half the width of the nail of your little finger held at arms length. None of the stars seen are naked eye stars, and there are many stars much fainter than Pluto. There are a couple of very faint galaxies, but external galaxies are hard to see through all of the intervening dust near the core of the Milky Way galaxy. But where is Pluto? Not in the center, mainly because I somehow entered the wrong date for Pluto's position. Pluto is near the right edge, a little less than halfway from the bottom of the image to the top. To find it, you have to look at several exposures made during the three hours that the telescope was making images. What you look for is a "star" that moves relative to the real stars in the image. This is the way Pluto was originally discovered, so it seems fitting to find it this way. If you click the image, you will be taken to a video we made that shows Pluto in six of the exposures. The video is only about 4 seconds long. Make sure you are in HD and full screen, click the start button, and then watch along the right side and lower half of the image for a "star" to move very slowly towards the edge of the frame. You may have to play the video several times before you are looking at the right spot to see the movement. Once you spot it, it's easy to see! You've now rediscovered Pluto. It does not move very far, but remember, it takes Pluto 247.68 years to make one orbit around the Sun! Pluto was discovered with a 13-inch, f5.6 astrograph not much larger than our 12.5 inch, f6.0 Newtonian. Discoverer Clyde Tombaugh had to blink a lot of images before he finally found it. Though at the time it was thought that the position for Pluto was predicted by perturbations in Neptune's orbit, it is now known that the "perturbations" were measurement error, and the discovery was purely by chance. From Pluto, the Sun will be essentially a point source, but it will be far brighter than a full Moon here on Earth. You can read a book by the amount of sunlight reaching Pluto's surface. NASA has a fun project called Pluto Time. For any given day, the app will tell you at what time of day that the light levels outside will match that on the surface of Pluto. Typically, it is only a few minutes after sunset, when it is surprisingly bright. You can find out your Pluto time here. The flyby of the New Horizons mission is scheduled for 11:47UT on July 14th. It will take months to download all of the uncompressed data, but compressed data will be relayed back to Earth relatively quickly. The flyby will also target Charon, Pluto's largest moon. James Christy discovered Charon in 1978 and proposed the name. In Greek mythology, Charon was the boatman that ferried souls across the river Styx. There is some discussion about the proper pronunciation of the name. The mythological character's name is usually pronounced with a "K" sound. But Christy had a different pronunciation in mind, and NASA agrees with it. Christy wanted to honor his spouse, who's name is Charlene (nickname Char). Charon, he said, should be pronounced with an "Sh" sound.

On June 11th I helped Andrea on a study of American Eels along a creek in Dickson county. Although we did not succeed in live-trapping an eel this particular trip, we did get to see some good habitat along the stream. One interesting resident was an extremely long-legged spider. A Slippery Elm overhung a small pool along the stream, and the spiders were on the branches of the elm.

These spiders are members of the longjawed orbweavers family (Tetragnathidae). They have very long cheliceral bases and fangs, and you can see these in the image at right and below. The cheliceral bases extend downward and outward. The spiders hang from beneath the branches. The two front pairs of legs, and the rear pair, are aligned with the branch. This makes them more difficult to spot. Although the body length is only around 1/2 inch long, the legs are impressively long! These spiders are probably Tetragnatha versicolor. I'm told that without examining some very small field characters these spiders are difficult to identify at the species level.

There were many of these spiders on the elm branches, most aligned with whatever branch they were on. There was a lot of variation in the color of the abdomen of the individuals we found. Though some looked identical in structure to the one shown, their abdomens were white with purple markings. These spiders build horizontal webs over the water. Insects emerging from the water's surface become caught in the webs. These webs are said to be superb mosquito catchers, and the spiders are beneficial in this way. It would be interesting to learn what drove the development of the extremely long front legs.

Sky Events for July 2015: Earth reaches aphelion, its farthest distance from the Sun, at 2:41pm CDT on July 6th. Evening Sky:

Venus and Jupiter begin the month close to each other in the western sky after sunset. Venus is much the brighter of the two. Venus will soon be passing between the Earth and the Sun and by the end of the month will show a striking large and thin crescent phase as shown at right. To see the crescent well you need to look at Venus just as soon after sunset as you can pick it out from the bright sky background. If you do that, the tiny thin crescent is visible even in a good pair of binoculars. Darkening the view with a filter will also help show crescent. Jupiter is low in the western sky in Leo this month, and spends much of the month close to Venus. Pluto sits like a grain of sugar in "the teaspoon" of Sagittarius this month. It will take a dedicated search with a large telescope to visually find it. Due to the large number of faint background stars, you will need a very good finder chart.

Look for Saturn in the southeastern sky at dusk about 30 degrees above the horizon at the beginning of the month. The planet will be in Libra this month. Saturn's rings have opened up to more than 24 degrees tilt, giving a wonderful view of the ring system through just about any aperture telescope. Saturn transits around 9:00pm CDT at mid-month, and you will get your best telescopic view around that time. Morning Sky: Look for Mercury low in the morning twilight at the beginning of the month, about 6 degrees above the eastern horizon. Begin looking about 45 minutes before sunrise. It will gradually sink back into the twilight glow as the month progresses. All times noted in the Sky Events are for Franklin, Tennessee and are in Central Daylight Time. These times should be pretty close anywhere in the mid-state area. Summer Messier Objects: Looking south on a clear midsummer night yields a treasure trove of Messier clusters and nebulae. The illustration below is made for July 15th at 10:00pm. You will want a clear, moonless evening far from city lights. First, look for Antares, the red giant that marks the heart of Scorpius, the Scorpion. The name Antares means, "rival of Mars." See if you can trace the tail of the scorpion down almost to the horizon, then back up to the two close stars that mark the stinger. These two stars are sometimes called the "cat's eyes." Due south look for the stars of Sagittarius. The brighter stars form an asterism known as "the teapot." Above the handle of the teapot you can see the four stars that form the asterism known as "the teaspoon." In a dark sky, the clouds of the Milky Way seem to boil out of the spout of the teapot. Above and to the right of the spout of the teapot is the radio source Sagittarius A*. It marks the center of our galaxy. There an enormous black hole with the mass of around 4 million times the mass of the Sun is thought to feed on any stars unlucky enough to wander too close. Nothing unusual is seen visually at this spot, but it's fun to imagine the beast within. This is a beautiful area to scan with binoculars, with many clusters and nebulae. See how far you can trace the Milky Way across the sky (easier if you're far away from city lights). Compare your view of the Milky Way to the image of the edge-on galaxy NGC 4565 we made in April of 2010.

Some of our favorite Messier objects reside in this part of the sky. One of the things that inspired me to build a 6 inch reflecting telescope in high school was an illuminated slide of the Eagle Nebula, M16, that was made by the 200" inch telescope on Palomar Mountain. You won't see the bright colors of these nebulae in a small telescope - the eye is very poor at detecting color at these very low light levels. But it's fun to try to spot the faintly glowing cloud. Another favorite is the Swan Nebula, M17. Here you can see a faint "swan" swimming in a pretty star field. You might also see if you can spot the dark lanes in the Trifid Nebula, M20. A nebula filter will help see detail, but will also tend to alter the appearance of the stars in the field. Above the spout of "the teapot" is Messier 8, the Lagoon Nebula. Don't leave this area without looking at the magnificent globular cluster Messier 22. Look for it slightly above and to the left of the star at the top of the teapot's "lid."

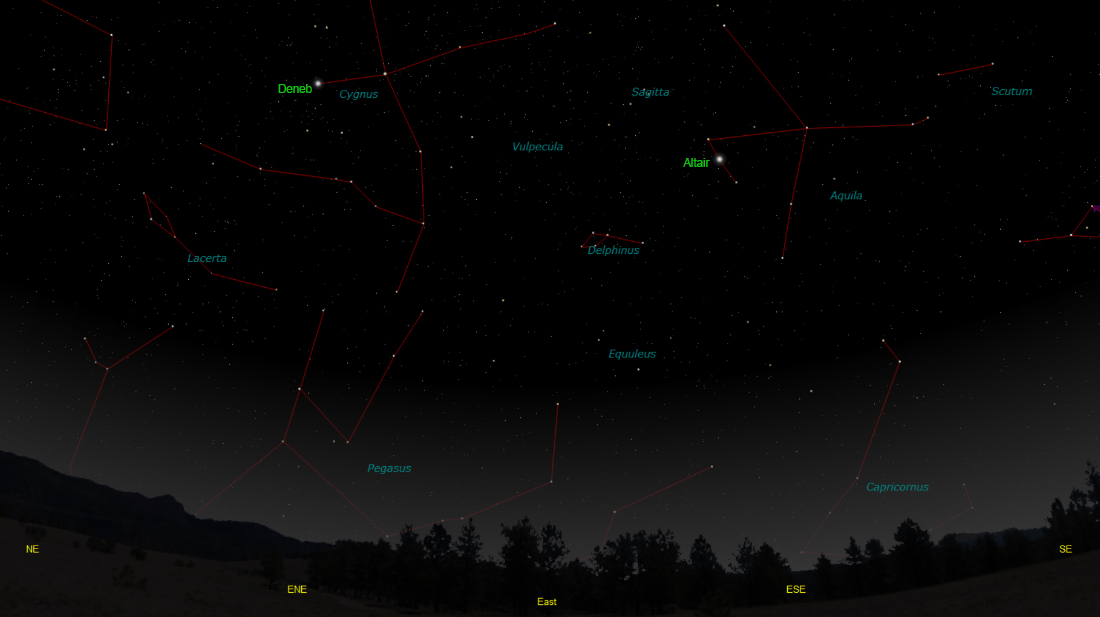

Constellations: The views below show the sky looking east at 10:00pm CDT on July 15th. The first chart shows the sky with the constellation outlined and names depicted. Star and planet names are in green. Constellation names are in blue. The second view shows the same scene without labels. Prominent constellations this month in the eastern sky are Cygnus, the Swan, with its bright star Deneb, and Aquila, the Eagle, with its bright star Altair. Below and to the left of Altair is the constellation of Delphinus, the Dolphin, looking like it's leaping over the eastern horizon. Above Delphinus look for the arrow-like form of Sagitta, the Arrow. Between Sagitta and Cygnus lie the faint stars of Vulpecula, the Fox.

On Learning the Constellations: We advise learning a few constellations each month, and then following them through the seasons. Once you associate a particular constellation coming over the eastern horizon at a certain time of year, you may start thinking about it like an old friend, looking forward to its arrival each season. The stars in the evening scene above, for instance, will always be in the same place relative to the horizon at the same time and date each July. Of course, the planets do move slowly through the constellations, but with practice you will learn to identify them from their appearance. In particular, learn the brightest stars (like Deneb and Altair in the above scene), for they will guide you to the fainter stars. Once you can locate the more prominent constellations, you can "branch out" to other constellations around them. It may take you a little while to get a sense of scale, to translate what you see on the computer screen or what you see on the page of a book to what you see in the sky. Look for patterns, like the stars that make up the constellation Cygnus. The earth's rotation causes the constellations to appear to move across the sky just as the sun and the moon appear to do. If you go outside earlier than the time shown on the charts, the constellations will be lower to the eastern horizon. If you observe later, they will have climbed higher. As each season progresses, the earth's motion around the sun causes the constellations to appear a little farther towards the west each night for any given time of night. If you want to see where the constellations in the above figures will be on August 15th at 10:00pm CDT, you can stay up till 12:00am CDT on July 15th and get a preview. The westward motion of the constellations is equivalent to two hours per month. Recommended: is beautiful, compact star atlas.A good book to learn the constellations is Patterns in the Sky, by Hewitt-White. You may also want to check out at H. A. Rey's classic, The Stars, A New Way to See Them. For skywatching tips, an inexpensive good guide is Secrets of Stargazing, by Becky Ramotowski.

A good general reference book on astronomy is the Peterson

Field Guide,

A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets, by Pasachoff. The book retails for around $14.00. Starry Night has several software programs for learning the night sky. Visit the Starry Night web site at www.starrynight.com for details.The Virtual Moon Atlas is a terrific way to learn the surface features of the Moon. And it's free software. You can download the Virtual Moon Atlas here. Cartes du Ciel is a great program for finding your way around the sky. It is also free, and can be downloaded here. Apps: We really love the Sky Safari Pro application described here. For upcoming events, the Sky Week application is quite nice. Both apps are available for both I-phone and Android operating systems. The newest version, Sky Safari 4, is available from Play Store or from i-tunes.The makers of Sky Safari 4 have a free app called Pluto Safari. You can get the latest info and run simulations for the New Horizons mission to Pluto with this app, and get the latest news and images from the mission. It's available for both iOS and android operating systems. With the closest approach to Pluto coming up on July 14th, it should be very useful.

Amphibians:

Recommended: The Frogs and Toads of North America, Lang Elliott, Houghton Mifflin Co

Insects:

For many people, one of the defining sounds of a summer night is the rhythmic chanting of katydids. For me the sound evokes memories of summer vacations when I was a kid. Our family often drove at night along state highways. The interstate system was still yet to come. Our car, like most cars then, did not have air conditioning, so the windows were down. As the highway wound through patches of forest the katydid calls grew louder, enveloped the car, then faded away. My brother and I stretched out on beds our parents made for us on the back seat and floor (no seatbelts then.) We drifted off to sleep to the comforting murmur of our parents' voices and the calls of the katydids, a lullaby.

The eyes of katydids are stunning, with the upper part yellow and the bottom a rich green. Only the males have the purple "cap." Katydids belong to the family Tettigoniidae. The call that is probably best known is that of the Northern True Katydid. It's in the subfamily Pseudophyllinae, and the species name is Pterophylla camellifolia. It ranges over most of the eastern United States. Northern True Katydids typically call from fairly high in the tree canopy, making them difficult to spot. The genus name, Pterophylla, literally means "wing leaf" and they are amazing leaf mimics. Compare the pattern in the katydid's wings in the top image above to the patterns in the leaflet in the lower right hand corner of the image. Northern True Katydids produce sounds by rubbing a sharp "scraper" at the base of one wing against a file-like row of "teeth" at the base of the other wing. Sometimes in large choruses the calls become synchronized. In this recording we made at Franklin State Forest in Marion County, a Northern True Katydid close to the microphone begins calling. Note how its call becomes synchronized with the ongoing chorus.

The False Katydids are in the subfamily Phaneropterinae. One common member of this subfamily is the Oblong-winged Katydid. These katydids have wings that are more elongated than the Northern True Katydid, and the call is a short raspy sound only about a third of a second long.The call sounds a little like a match being struck. In this recording Northern Cricket Frogs are heard calling in the background. The katydid gives only a single note. Oblong-winged Katydids usually are a bright green color, but can also occur in the yellow form shown in the image at left. We find the yellow form to be rarer. Pink forms have also been found.

The calls of coneheads are conspicuous on midsummer evenings. Two common species of coneheads in Tennessee are the Robust Conehead and the Nebraska Conehead. Both species can be either green or a brown in color. Both usually call from weedy vegetation with their head down, as shown in the image at right, ready to drop into the ground cover if alarmed.Coneheads are in the katydid family (Tettigoniidae), which also includes the True Katydids, the Meadow Katydids, the Shieldback Katydids and the False Katydids. The genus is Neoconocephalus. The easiest way to locate coneheads is by listening for their calls. Just drive a few back roads that pass by weedy fields at dusk or later and you should hear them. The Robust Conehead is the larger of the two species and is between two and three inches long. It has a very long, rasping call on one pitch. Like a bad musician, it seems to try to make up in sheer volume what its song lacks in complexity. As you drive by you can sometimes hear the call doppler-shifting downward. The call has a peak frequency of around 8 kHz, and you can listen to one we recorded by clicking here. There are two cuts - the first cut records the sound as you might hear it at a distance, and includes Common True Katydids in the background. The second cut records the sound as you might hear it if one is calling right beside the road.

The name Nebraska Conehead is a little misleading, as the range of this species also includes a wide area of the eastern United States. A little smaller than the Robust Conehead, it measures between 1-3/4 inches to 2-1/4 inches in length. The call of the Nebraska Conehead is also a raspy note on one pitch, but the length of each call lasts only between 1-1/2 to 2 seconds, with a pause of about one second in between calls. Its call peaks around 10 kHz. To listen to a recording of a Nebraska Conehead , click here. Seen close up, the eyes of both species are quite interesting. If you happen across a conehead that is not calling, look carefully at the underside of the cone and observe how it is marked. These markings are a useful way to distinguish between species. See the reference at the bottom of this section for help in identification.

The trigs form another interesting group. These small crickets belong to the subfamily Trigonidiinae (hence the name). They are also known as the sword-tailed crickets. Shown at right is the Columbian Trig. Only about 1/4 of an inch long, these tiny crickets make sounds that many people have heard all their life without knowing the identity of the caller.A chorus has the rhythmic quality of sleigh bells. Because they tend to blend in with the other sounds of a summer night, you may have to concentrate to pick them out of the many other insect noises on a typical July or August night. We made this recording in our front yard, and since seem to hear them everywhere we go.

Archives (Remember to use the back button on your browser, NOT the back button on the web page!) Natural Calendar November 2014 Natural Calendar September 2014 Natural Calendar February 2014 Natural Calendar January 2014 Natural Calendar December 2013 Natural Calendar September 2013 Natural Calendar February 2013 Natural Calendar January 2013 Natural Calendar December 2012 Natural Calendar November 2012 Natural Calendar September 2012 Natural Calendar February 2012 Natural Calendar December 2011 Natural Calendar November 2011 Natural Calendar September 2011 Natural Calendar February 2011 Natural Calendar December 2010 Natural Calendar November 2010 Natural Calendar September 2010 Natural Calendar February 2010 Natural Calendar December 2009 Natural Calendar November 2009 Natural Calendar September 2009 Natural Calendar February 2009 Natural Calendar December 2008 Natural Calendar November 2008 Natural Calendar September 2008 Natural Calendar February 2008 Natural Calendar December 2007 Natural Calendar November 2007 Natural Calendar September 2007 Natural Calendar February 2007 Natural Calendar December 2006 Natural Calendar November 2006 Natural Calendar September 2006 Natural Calendar February 2006 Natural Calendar December 2005Nature Notes Archives: Nature Notes was a page we published in 2001 and 2002 containing our observations about everything from the northern lights display of November 2001 to frog and salamander egg masses. Night scenes prepared with The Sky Professional from Software Bisque All images and recordings © 2015 Leaps

|